As Athena was returning from the mountain of Penteli, on the periphery of Attica’s landscape, carrying a rock for the fortification of the Acropolis, flying ravens informed her that Kekropos’ daughters had opened the basket she had entrusted them to look after. Erichthonios, the baby son of Hephaestus and future king of Athens who was born half human and half snake, was sleeping inside this basket. Athena was upset by the unpleasant news and the rock fell from her hands. Since then, ravens are black, while the Athenian landscape acquired Lycabettus hill, the city’s highest peak.

In Athens, the first morning light (= lyki) is to be seen behind this rock, thus signifying the beginning of each new day and offering the hill its very name. The origin of the word ‘Lycabettus’ can also be traced in the pre-Hellenic, ancient Egyptian noun lykavas (= the path of light, the route of the sun, the year).

Over the centuries, Athena’s rock- the rock of light- became an olive grove, a grassland for sheep, a quarry, an artillery base, a quarry once again and reached modern times as a weathered, eroded and abandoned urban boulder prey to the state’s indifference and short-sighted exploitation. Fortunately enough, Lykabettus hill received in the early 1960s the attention of Anna Synodinou, a significant Greek actress, who proposed to host a new open theater on the hill’s wounded northern slope. The actress was seeking a new artistic shelter after having left the Greek National Theater and she found on the deserted quarry of Lykabettus the ideal place.

The path leading to St. Isidoros’ church narrowed even more as you were approaching the pit. The debris from the construction of the Hilton hotel were placed there. We climbed. Oh Lord! A wasteland. A dry place, a junkyard; garbage everywhere, a dangerous environment even in broad daylight. A few daffodils and two or three mourning cypress trees were the only vegetation.[1]

Yet that wild landscape, rough and wounded, secluded yet close to the city centre, a quiet space within a bustling city, was perfect for a new ancient drama theater built following the standards of the ancient ones. The quarry is a place of grandeur within its very wilderness. Its aesthetics, Doric, sharp, imposing, surprise and frighten perhaps, matching the spirit of an ancient drama. The quarry has the stone, the material that significantly enhances sound through reflection and helps acoustics. The quarry also includes hubris; the insolent and arrogant exploitation of natural resources and the abandonment of the dissolved landscape to become a dump and a ruin. With the new theater, this wild, coarse, disgraced place would become noble; a place of sublime art and of catharsis.

The aim of Anna Synodinou was not merely to construct a new theatrical establishment but to create a core of artistic activity that would focus on Greek drama and ancient Greek tragedy. The theater would present exclusively the works of Greek playwrights while its operation would be accompanied by that of a drama school. This initiative essentially offered Athens the opportunity to acquire a second powerful theatrical and cultural pole that would operate complementary to that of the Acropolis and the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. Moreover, it would render Lycabettus- albeit belatedly- a reference point for the cultural and social life of the city. The hill’s steep slope and the fact that it stood outside of the ancient city’s walls, prevented it from constituting part of the city’s structure, of its admirable architectural works and the notable political and collective fermentation that took place in the neighboring hills of the Acropolis, Filopappou and Pnyx. Now Lycabettus had its own chance.

The procedures for the establishment of the theater began in May 1964. The land of the old quarry belonged to the Greek Church. 12 acres were leased to Synodinou for every summer season for a period of 20 years. The actress contacted the Greek Tourism Organization (EOT) seeking financial support for her project. The Organization refused to grand her a loan. However, the Ministry undertook the cost for the construction of the theater after assuring the ownership of the land, through property exchange with the Church Property Management Organization. Thereby, the Tourism Organization would be the only owner of the theater and it would assign it to Synodinou for three months every year. (defeat no1)

Synodinou studied the area for some time along with significant artists, playwrights and composers in order to form a clear opinion about the qualities of the theater that needed to be built on the quarry. She concluded that the theater should have a circular orchestra as opposed to the semicircular one of the Herodus Atticus Odeon and a big stage with an open background, free from the restrictive, permanent scene of the surrounding rocks. The acoustics were studied thoroughly as well. Synodinou recited repeatedly from several spots of the area in order to identify the stage’s ideal orientation to ensure the space’s optimum audio performance. When the data was gathered, Synodinou commissioned the Greek visionary architect Takis Zenetos to design the theatre.

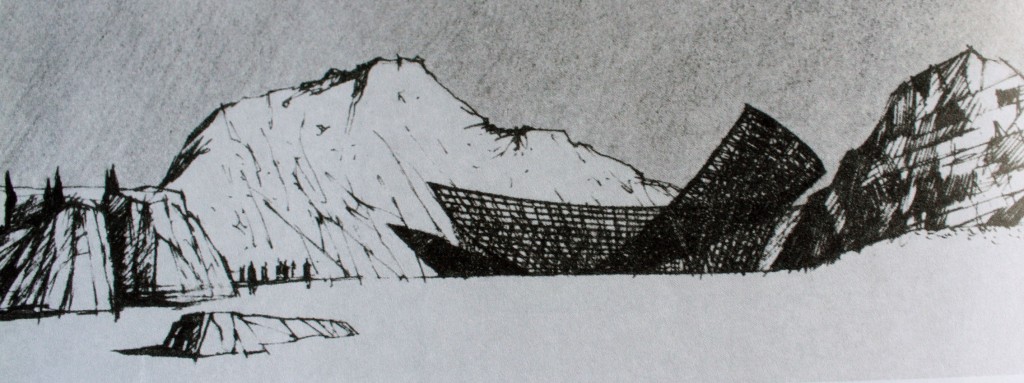

The architect named his proposal Clam Theater. A pedestal of reinforced concrete would have been constructed under the theater’s orchestra. The 5000 seat auditorium would have been supported on a cantilever based on this pedestal. Without columns and with no further supporting systems the auditorium would seem to hover above ground. All the auxiliary functions – dressing rooms, restrooms, warehouses, electrical installations – would have been placed underneath the concrete level along with the drama school. The study also included vehicle access to the theater through a newly designed road as well as a parking lot. The total cost of the project was estimated at 7.000.000 drachmas and the plans were submitted to the Greek Tourist Organization in January 1965.

The proposal was considered unacceptable by a number of relevant organizations, associations and the press for a number of different reasons. They argued that the proposed theatre would not blend into the surrounding landscape, that the access to the theater was not studied adequately and, instead, an overall development design proposal was needed, that the public would have to climb on a sloppy hill in order to see a theatrical performance, that the implementation of this proposal would destroy the existing plants (in a bald landscape) or that the aesthetic view of the hill would be destroyed for those who would see it while travelling by plane! An official meeting between the Greek Tourist Organization and representatives of architectural and urban planning bodies concluded that the plan proposed by Zenetos was excessive, that it could not be carried out and so, that the Tourist Organization needed to launch a nationwide architectural competition for the development of Lycabettus hill. (defeat no2)

However, the field preparation works had already started in the plot and Synodinou had prepared her performances for the summer of 1965 with the previous approval of the Tourist Organization. Therefore, the two sides signed the final leasing contract noting that, in case the theater could not be completed till the summer of 1965, the Tourist Organization would undertake the construction of a temporary prefabricated theater of 3000 seats at the command of Synodinou for the upcoming theatrical season. This arrangement satisfied both sides at the time while it also included the prospect for the development of a permanent structure at some point in the future. The Tourist Organization even announced an architectural competition for a leisure and recreational park in the hill, which never went through.

In March 1965 Zenetos submitted his architectural study for a temporary, prefabricated, 3000 seat theatre. Their proposal was entitled “Temporary Theatre, Athens” and was published in the Volume World Architecture 4. It drew inspiration from the form of the radio telescope. It was a steel structure that landed on the large void of the old quarry, separated from the surroundings but complementary to it, leaving the existing moonscape intact. The shape of the theatre was a parabolic cone. It allowed the unobstructed view of the stage from any part of the auditorium and did not create any acoustic shadows. Every additional, auxiliary function was placed underneath the auditorium, below the orchestra’s level. The wooden seats and the earthen ground of the orchestra favoured the theatre’s acoustics.[2] Every construction element was designed to enable possible future transfer and reconstruction in another location. However, there was no transfer or replacement of the theatre which, although temporary, lies still on the hill’s north side for now almost half a century.

The construction company that was commissioned to carry out the project was different than the one Zenetos had suggested and the theatre’s implemented form is significantly different from the one in the architectural plans, as Zenetos himself states in his article in ‘World Architecture 4’. However, he argues that the form’s geometry, its purity and the transparency of the load bearing structure manage to reflect the relation between the theater and its surrounding moonscape.[3] Ιn her biography, Anna Synodinou mentions though that, feeling deeply disappointed from the final structure, Zenetos never visited Lycabettus Theater again.

The performance that inaugurated the new theatrical scene of Athens was ‘Antigone’ by Sophocles on 12 June 1965. The theatre operated freely and creatively for three summer seasons hosting ancient plays. This was short lived as the Greek Military Dictatorship (1967-1974) that was imposed in April 1967 signified the end of Lykabettus Theatre in the way that Synodinou had envisioned it.

The Greek Tourist Organization, which was responsible for the approval of the theatrical programme for each season, censored the play of ‘Prometheus Bound’ that Synodinou was planning to perform in the summer of 1967 because – according to the censorship officer – Prometheus is insolent and states that he does not respect the gods. Following this, the Organization occupied the theater for various activities during the summer period and licensed it to Synodinou for a few days during October. The performance of ‘Electra’ in October 1967 was the last to be performed in the theater. A few weeks later the regime had Synodinou’s passport confiscated so as to prevent her form going on tour abroad.

The actress declared her opposition to the undemocratic regime publicly and refused to participate in any theatrical activity for as long as freedom of speech was persecuted. In May 1969, she recorded a message of protest, which was transmitted by several international media. In November 1969, she participated in a BBC broadcast against the Greek Dictatorship and the violation of human rights. As a reaction to her movements, the oppressing regime terminated her lease of Lycabettus Theater and confiscated the property.

The trucks came and took my soul. They took Poetry; Antigone, the Ecclesiazusae, Praxagora, Eleni and Teucer, Lyssistrati; they took the women fighting for Peace; they took Electra, Orestes, Iphigenia and the women of Avlidas; they took the dreams, the tears and the laugh of the spectators…[4] (defeat no3)

Lycabettus Theater has operated since then as a rather popular performance stage for theatrical plays of a varied repertoire and divergent music concerts. It has a flexible stage, an excellent view, a spacious parking lot and it is easily accessed. It is a significant reference point for the summer artistic activities in Athens and the number one memorable place for the first concert of almost every teenager. However, Lycabettus Theater never became what its inspirers had envisioned. It never became a nucleus of ancient drama study, exploration, teaching and promotion neither a sample of innovative architectural expression, even though the conditions were more that propitious for it to become both. Lycabettus Theater is, in a way, a place of both aspiration and disappointment, a place of harmony and distress, where the Apollonian joins with the Dionysian just like the ancient Greek tragedy which is Antigone and Cassandra at once.[5]

Kanelia Koutsandrea

[1] Άννα Συνοδινού, Πρόσωπα και Προσωπεία, εκδόσεις: Αδελφοί Βλάσση, 1998, σελ.255, 256.

[2] During the construction a number of stands were added at the auditorium, the seats were made of plastic rather than wood and the orchestra’s ground covering was not made of clay as the initial plans indicated.

[3] Takis Zenetos, “Temporary theater, Athens», World Architecture, 4, London: Studio Vista, 1967, p. 188-191

[4] Συνοδινού, Πρόσωπα και Προσωπεία, σελ. 346

[5] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Zisis Sarikas, Vanias publications, Athens, 2008.

Image references:

Feature image: The theatre’s plan is from Takis Zenetos, “Temporary theater, Athens», World Architecture 4, London: Studio Vista, 1967, p. 189.

Images 1,2: Άννα Συνοδινού, Πρόσωπα και Προσωπεία, εκδόσεις: Αδελφοί Βλάσση, 1998, σελ.266.

Read the original Greek article here.